(Lea Susemichel)

Best Friends Forever

Women are two-faced gossips; true friendship is masculine, or so the age-old bias would have us believe. Not so, says Lea Susemichel. For a politics of girlfriendship.

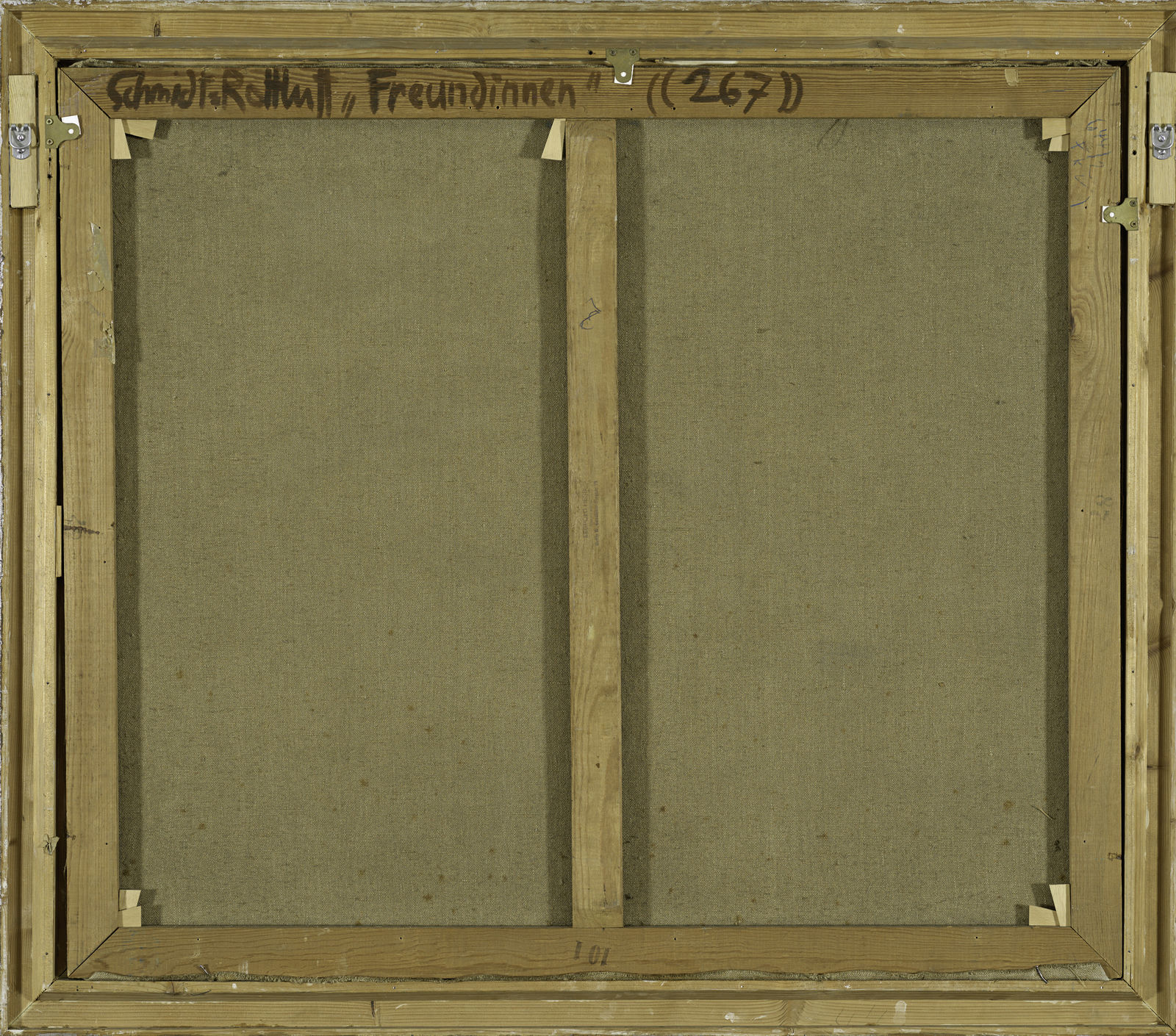

“Friends” was a line of pink-and-purple LEGO playsets created especially for girls. It is generally girls, not boys, who refer to one another as “BFFs” (Best Friends Forever). Who make friendship bracelets following instructions from teen magazines, then look to those same pages for advice on how close friendships between girls might survive competition from first boyfriends. A decades-old German women’s magazine calls itself Freundin (Girlfriend), and just as successfully sells feelings of trust, intimacy and connection. Novels and self-help literature both attend to and reinforce the underlying cliché that girls and women are responsible for emotions and consequently experience more intense friendships, while men remain stubbornly unable to open up. Though pop and day to day culture purport a number of ways to celebrate female friendship, a closer look surprisingly reveals that, culturally speaking, friendship remains a deeply masculine concept all the same.

Barbie, not Buddy. Apart from the girlfriend-centric models of Sex and the City, what pop culture usually provides – in films, TV series, and elsewhere – is mostly stereotypes of rival female neighbours and Desperate Housewives who relentlessly pick at each other, only speak about men, and even fight over them. As the so-called Bechdel test shows, films featuring firstly, at least two female characters with names; secondly, female characters that speak with one other; thirdly, female characters that speak about something other than a man, continue to be the exception. Meanwhile, classic “buddy” movies – the genre of two people sticking together through thick and thin – almost always feature exclusively male actors. (Rare counter-examples include the spectacular road movie Thelma and Louise and Beaches, the 1980s tearjerker starring Bette Middler). Paradoxically, the same children lured to the cult of glittery-hearted girlfriends are also introduced to the perfidious significance of the much-evoked “catfight”: even the Barbie animated series depicts girls and women as scheming snakes.

Side by side? For all that, empirical studies of social support and friendship still show women’s friendships to be more common, more deeply felt and more satisfying than friendships between men; that women consider their friendships more important and that they also offer more concrete support than those between men.

Another, very real obstacle to intimate male friendship is homophobia. While female friends have been (and continue to be) stigmatised as lesbians, physical closeness and mutual affection between males is even more taboo. Even the term “bosom friend” suggests women are more likely to be granted physical, even homoerotic intimacy.

In making such comparisons, it is also important to stress that these “female” and “male” models of friendship are traditional socio-cultural constructs that are by no means necessarily tied to any essential biological gender identity. There are of course plenty of nasty male gossips and women who are deadly competitive. One should likewise avoid glorifying women as free of malice, or their friendships as a sit of constant harmony and mutual empathy – like male friendships, they are definitely not that.

Solidarity & sisterhood. There have fortunately been many attempts to celebrate friendship as lived solidarity and sisterhood, with one example being the call to transform Valentine’s Day into a feminist “Girlfriends Day”. The friendship between women is thought to be a key resource not only in the common struggle for emancipation, but above all for one’s own life. A woman’s circle of friends can serve as an elective family that can replace compulsory relatives if necessary and, ideally, offer a kind of social security. And apart from the real support girlfriends offer one other, they are above all beloved female companions, figures indispensable to one’s own happiness.

The significance of girlfriendship is given far too little attention on the whole, a fact that even the latest “affective turn” in the humanities and social sciences has done little to remedy. Despite broader recognition of “emotional labour” as an important social and political factor even beyond the field of gender studies, the contribution of women is still largely considered only in terms of reproductive or care labour. There is research into the ways in which women’s labours of love and family and friendship care activities might compensate for neoliberal failures, or how their affective labour is even marketed as a service. By contrast, the poststructuralist figures of a “politics of friendship”, or concepts of “affective politics” developed with cues from the writings of Jacques Derrida, remained secretly something of a male concept. At the very least, there is little to no research on the explicit role that women in particular – the people primarily charged with maintaining social relations – play in resistance and solidarity-based or subversive networking. That said, maintaining such girlfriendships is something that goes beyond the political, as it is also personally of interest. Even Eva Illouz, the great love researcher, has recently shifted focus to friendship and praises it as the more valuable emotion. One study claims to have found that regular contact with good friends is even healthier than giving up smoking. This is true regardless of gender. As is, by the way, the decisive criterion for calling someone a best friend: a good feeling that comes from this person recognizing and respecting you in your own identity.