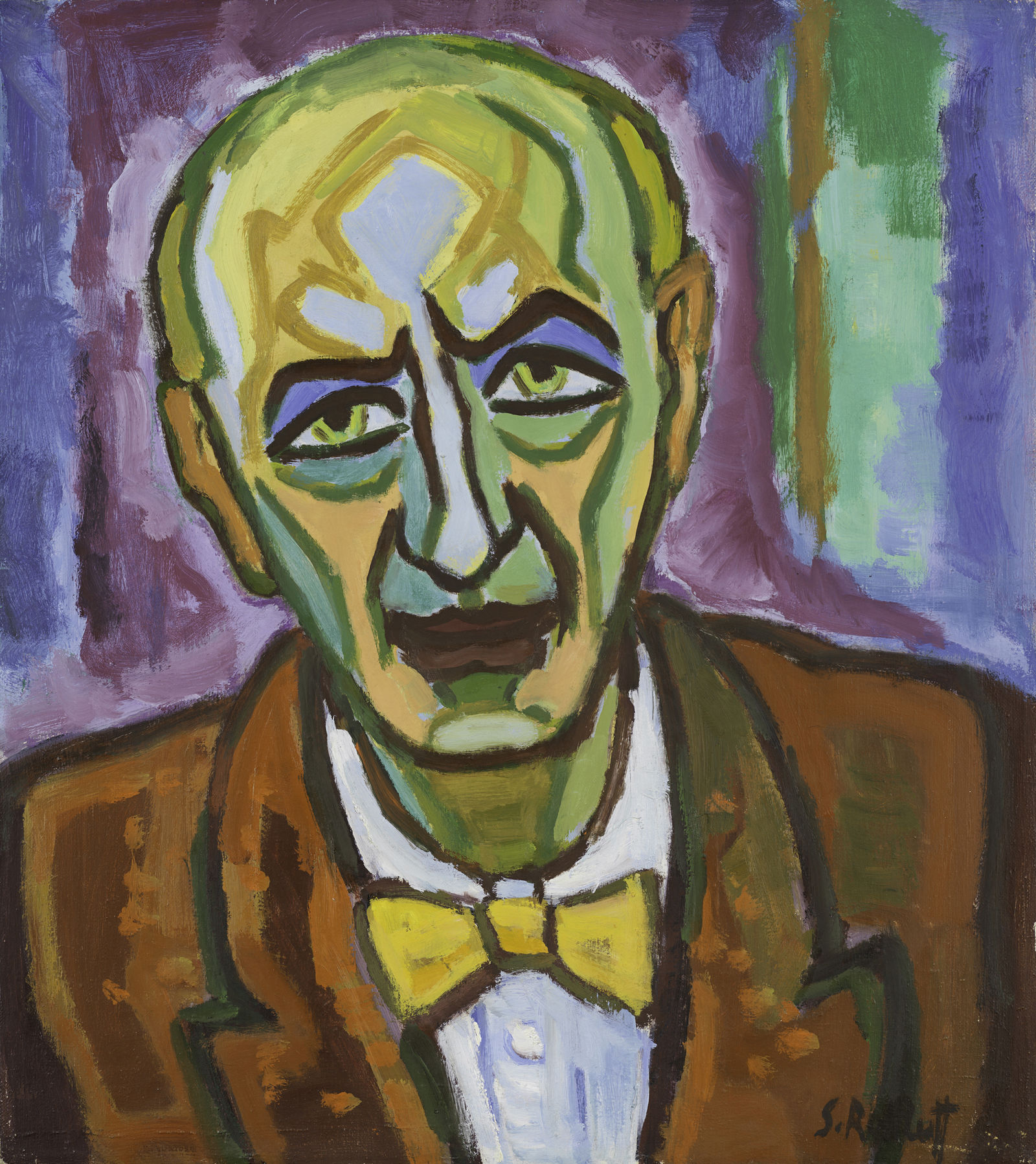

Portrait

by Irene Bretscher

16 images

Nowadays users of social networks such as Instagram or Facebook stage their own digital identities by presenting themselves publicly through their portraits, appearing in photos, and posting selfies. Their followers like them and leave comments as well as criticism.

Before the invention of photography in the nineteenth century, however, only people in positions of power were able to have their portraits painted. Rulers wanted to establish an omnipresent sense of their own importance. With the invention of photography, the painted portrait lost its monopoly. This was not the only reason why the Brücke artists pursued different aims in their portraits; they also wanted to transfer their emotional perception of their friends onto the canvas, or to show how they were feeling in their self-portraits.

One such example was in 1911, when Karl Schmidt-Rottluff painted the face of his friend, the Hamburg art historian and collector Rosa Schapire, in deep red tones. The colouring underlines Schapire’s self-confident and astute character. She advocated for the rights of women, and had already published the anti-capitalist text Ein Wort zur Frauenemanzipation (A Word on Women’s Emancipation) back in 1897. With this work she became one of the first women in Germany to receive a doctorate.

A portrait always shows the model through the eyes of the artist. It gives us insight into the way the painter views the model, and is therefore a reflection of their gaze. As women were denied access to the art academy at the beginning of the twentieth century, the male gaze dominates the art of this period. In nudes, the female body was often portrayed in a coquettish, eroticized pose or situated in nature, which was supposed to substantiate its grace and beauty.