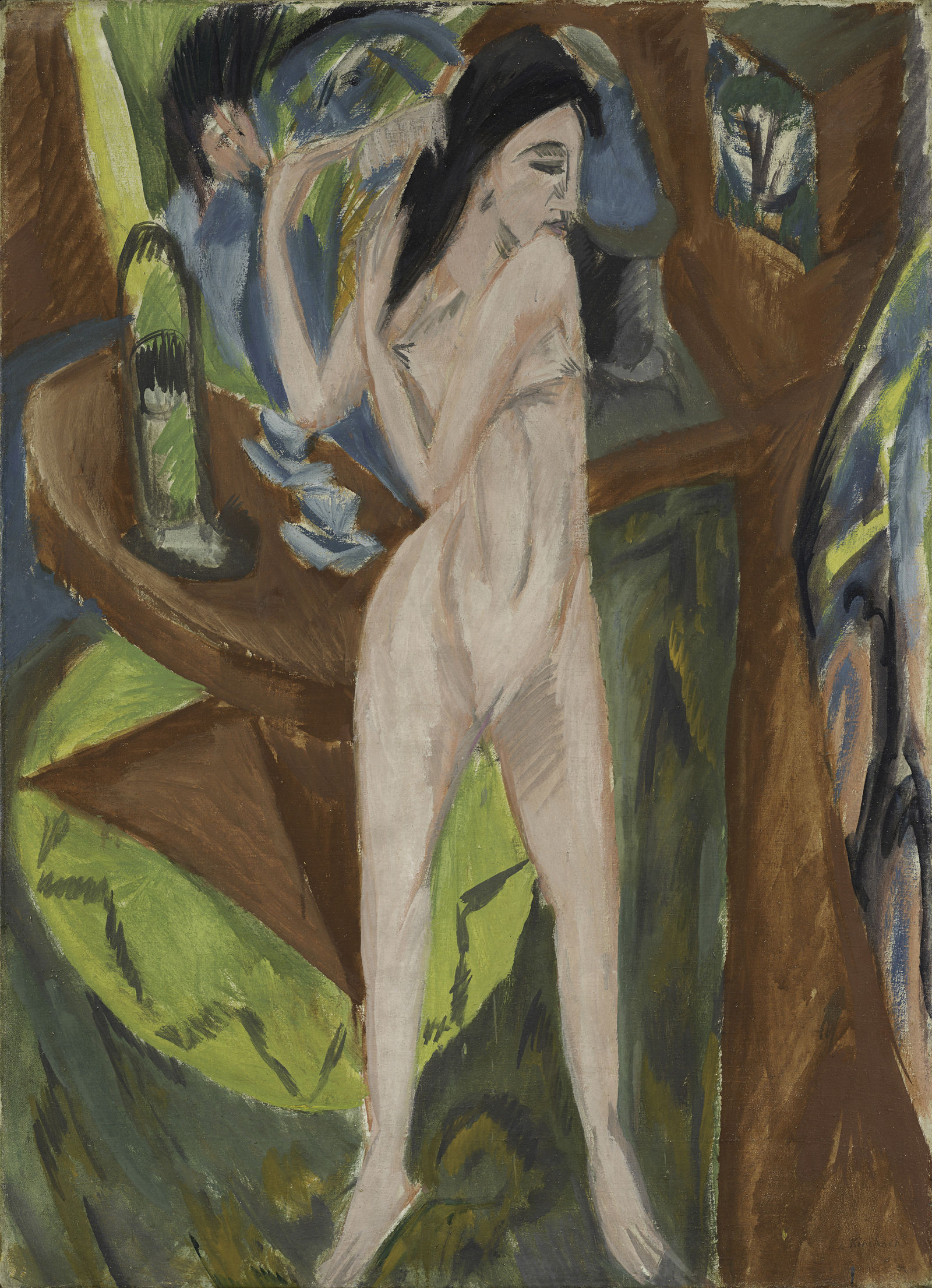

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Sich kämmender Akt

Rahmenmaß 146,5 × 111 × 5,5 cm

Provenienz

Das Gemälde wurde 1924 mit 23 weiteren Werken aus der Frankfurter Sammlung von Rosy Fischer an das Städtische Museum für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe in Halle verkauft (vgl. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Im Cafégarten, Inv.-Nr. 1/66). Im Kaufvertrag wurde vereinbart, dass von der Stadt Halle an Rosy Fischer (1869–1926) und nach ihrem Tod auch an ihre beiden Söhne, bis 1944 eine Rente zu zahlen sei. Diese Vereinbarung wurde aufgrund der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung der Söhne nicht bis zum festgelegten Zeitpunkt eingehalten. In der Nachkriegszeit erhielten sie deswegen eine finanzielle Entschädigung. Nachdem das Gemälde im Juli 1937 in Halle im Rahmen der nationalsozialistischen Aktion Entartete Kunst beschlagnahmt worden war, übernahm es 1940 der Kunsthändler Ferdinand Möller (1882–1956) vom Deutschen Reich. Entgegen seines Auftrags veräußerte er das Gemälde nicht ins Ausland, stattdessen verblieb es in seinem Besitz. Nach seinem Tod behielt es seine Ehefrau Maria Möller-Garny (1886–1971) noch bis 1970. In diesem Jahr gelangte es zur Auktion bei Kornfeld und Klipstein in Bern, aus der die Galerie Kornfeld es selbst erwarb. 1971 konnte es hier für die Sammlung des Brücke-Museums angekauft werden.

Exhibitions (selection)

- Der Angriff der Gegenwart auf die übrige Zeit. Künstlerische Zeugnisse von Krieg und Repression, 2023/24, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

Flucht in die Bilder? Die Künstler der Brücke im Nationalsozialismus, 2019, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

Die Brücke 1905–1914, 2018/19, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden

Großstadtrausch – Naturidyll. Kirchner – Die Berliner Jahre, 2017, Kunsthaus Zürich

... die Welt in diesen rauschenden Farben. Meisterwerke aus dem Brücke-Museum Berlin, 2016/17, Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte Oldenburg

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Retrospektive, 2010, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Christian Rohlfs. Die Begegnung mit der Moderne, 2006, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

Literature (selection)

- Leopold Reidemeister, Das Brücke-Museum, Berlin 1984.

Magdalena M. Moeller, Das Brücke-Museum Berlin, Prestel, München 1996.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke. La nascita dell´espressionismo, Ausst.-Kat. Fondazione Antonio Mazzotta Milan, Mazzotta, Milano 1999.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Die Brücke. Meisterwerke aus dem Brücke-Museum Berlin, Ausst.-Kat. Brücke-Museum Berlin, Hirmer Verlag, München 2000.

Javier Arnaldo, Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke. Die Geburt des deutschen Expressionismus, Ausst.-Kat. Berlinische Galerie, Hirmer Verlag, München 2005.

Javier Arnaldo, Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke. El nacimiento del expresionismo alemán, Ausst.-Kat. Museo Thyssen-Bornesza Madrid/Fundación Caja Madrid, Madrid 2005.

Brücke. El naixement de l'expressionisme alemany, Ausst.-Kat. Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya Barcelona, Lunwerg, Barcelona 2005.

Dirk Luckow, Magdalena M. Moeller, Peter Thurmann (Hg.), Christian Rohlfs. Die Begegnung mit der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat. Kunsthalle zu Kiel / Brücke-Museum Berlin, Hirmer Verlag, München 2005.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke-Museum Berlin, Malerei und Plastik. Kommentiertes Verzeichnis der Bestände, Hirmer Verlag, München 2006.

Magdalena M. Moeller und Rainer Stamm (Hg.), ... die Welt in diesen rauschenden Farben. Meisterwerke aus dem Brücke-Museum Berlin, Ausst.-Kat. Landesmuseum Oldenburg, Hirmer Verlag, München 2016.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke Museum Highlights, Hirmer Verlag, München 2017.

Christian Philipsen i. V. m. Thomas Bauer-Friedrich (Hg.), Bauhaus Meister Moderne. Das Comeback, Ausst.-Kat. Kunstmuseums Moritzburg Halle (Saale), E.A. Seemann Verlag, Leipzig 2019.

Meike Hoffmann, Lisa Marei Schmidt, Aya Soika für das Brücke-Museum (Hg.), Flucht in die Bilder? Die Künstler der Brücke im Nationalsozialismus, Ausst.-Kat. Brücke-Museum , Hirmer Verlag, München 2019.

Details

Tags

Bildgattung: Figurenbild, Szene, Akt

Schlagwort: Interieur

Album: Frauen, Rückseiten

GND

Referenz: Außereuropäische Kunst

Iconclass

sich unbekleidet, (fast) nackt zeigen

stehende Figur – AA – weibliche Figur

Kamm, Bürste und andere Utensilien für die Haarpflege – AA – (für) Frauen

Teppich, Vorleger, Brücke

Bild, Gemälde

Tisch

Hausinneres

Möbel und Hausrat

Haarpflege

Inscription/Signature

Signiert unten rechts:

EL Kirchner (Signatur)

Nicht bezeichnet (Bezeichnung)

Inventory Number

7/71

Catalog Number

Gordon 361