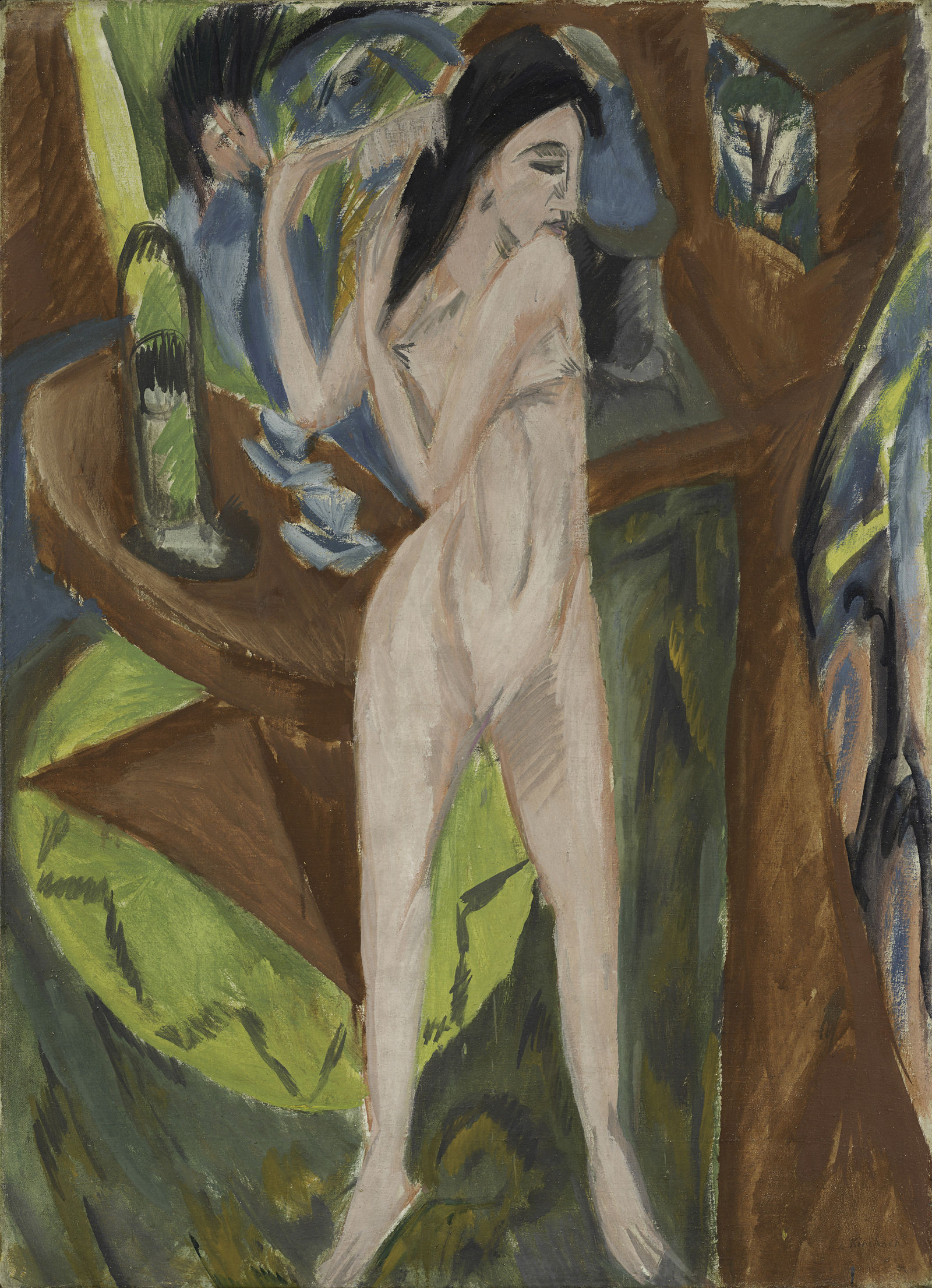

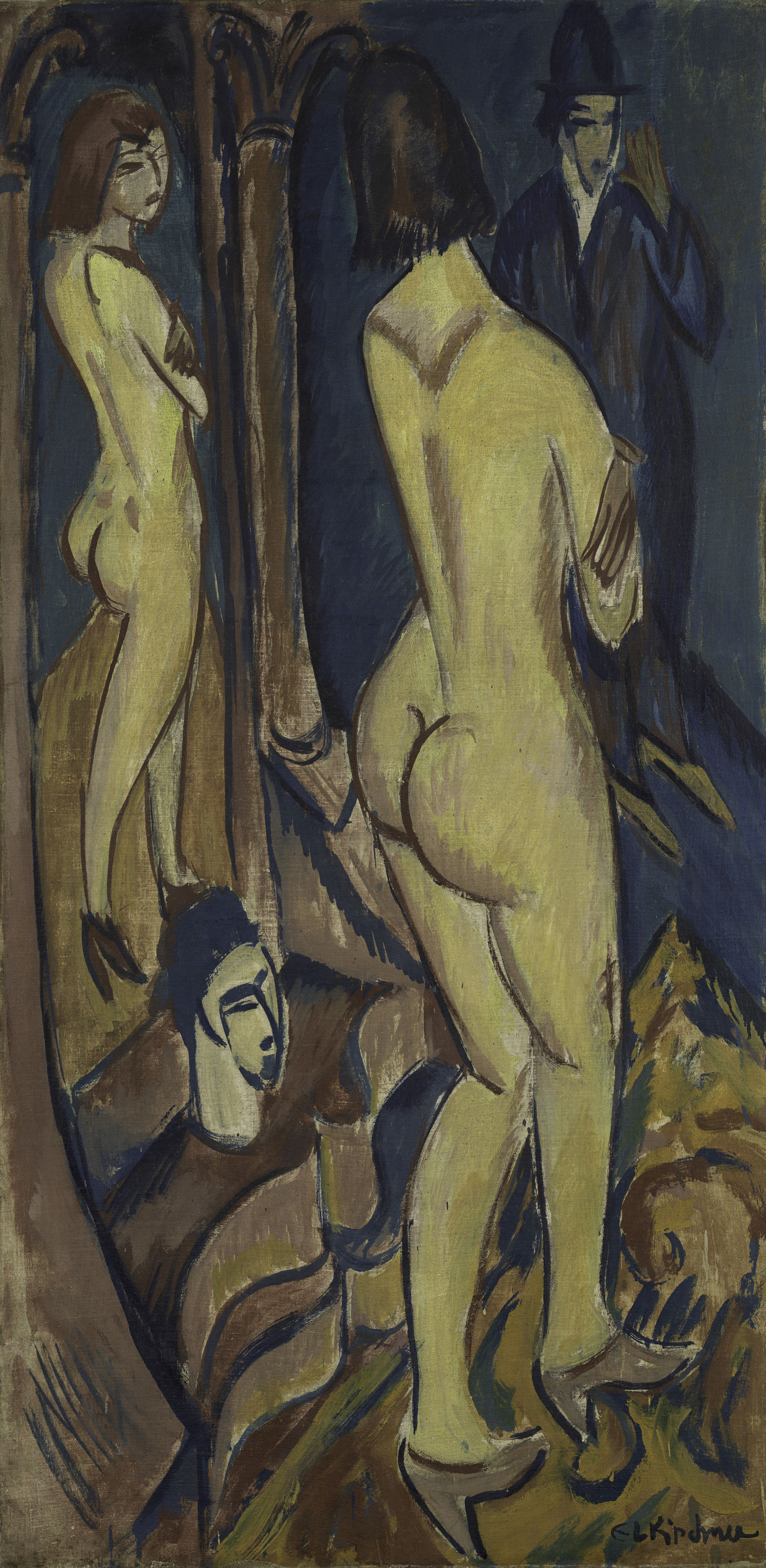

We are all familiar with this gaze: the one that gawks at female cleavage unsolicited, the one that sweeps over female curves in a tracking shot with relish, the one that peeks through the keyhole voyeuristically, the one that looks at short skirts disapprovingly… Art history in particular, as well as the collection of the Brücke-Museum, is teeming with depictions in which female bodies, whether naked or clothed, become objects of a male gaze. But what exactly is this “male gaze”, which most people today consider sexist, all about?

The concept of the male gaze originates from film studies and refers to the phenomenon in which men appear as active observers and women are consequently reduced to passive objects. The British film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the term in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” from 1975, in which she wrote: “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they could be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.”

The English art critic John Berger was already interrogating our Western capitalist perspective in his book Ways of Seeing back in 1972. He focused on the role of women in particular. On the basis of depictions of nudes in Western painting, he established that women’s bodies are predominantly staged as objects in order to gratify the male gaze. For Berger, this state of affairs was the result of the societal patriarchal power structure in which women were effectively regarded as the possessions of men. He described the consequences of this for male and female self-perception as follows: “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relationships between men and women, but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

The male gaze is therefore not only exercised by those of male gender; in a male-dominated, sexist society it concerns us all. Our perception has been shaped by the constant presence of images in the media that correspond to this gaze. There has also been repeated criticism of the concept of the male gaze: because it assumes the existence of only two genders – and heterosexual ones in addition to that – it does not take into account the perspective of LGBTQIA+ people. There is also no mention of factors such as racism, which can often heighten objectification. For a while now, the theory of a “female gaze” has been increasingly discussed, as advocated by French film scholar Iris Brey among others. She maintains that it should not simply be viewed as a reversal of its male variant, where the male body is now turned into an object of desire. Instead, in the female gaze, all bodies should become subjects of desire. The asymmetry in power relations that characterises desire in the male gaze is replaced by an aesthetic of equality and commonality.

Sonja Eismann is the co-editor of Missy Magazine and researches and writes about feminism and (pop) culture