Many people first associate this term with a polyphonic musical arrangement in which voices begin singing one after another to form a harmonious whole with a common, but staggered melody. The first voice serves, in a sense, as the guiding principle.

When elucidating a concept, it is sometimes helpful to trace the history of the term’s use. Canon derives from the Latin canon, meaning “rule” or “norm”. Which in turn derived from the Greek, where it referred to that which is exemplary or authoritative. And even before that, it had been adopted as a loanword from the Hebrew, denoting a reed that served as a standard of measure.

When people speak of canons in the context of art, literature, music, or film today, the term entails an attribution of quality – of value and importance. The question underpinning these imagined and, on occasion, actually printed catalogues is something to the effect of: What embodies artistic brilliance and will continue to be relevant in ten, a hundred, or even a thousand years to come?

Upbringing, education, cultural institutions, and media all hold sway over who is embraced by and who is left out of the canon. Books and paintings included in school curricula already convey to children a sense of what constitutes “good” and “important” art – and also what remains unknown. The politics of a museum’s collections and exhibitions also determine what is held in high esteem and even made visible in the first place.

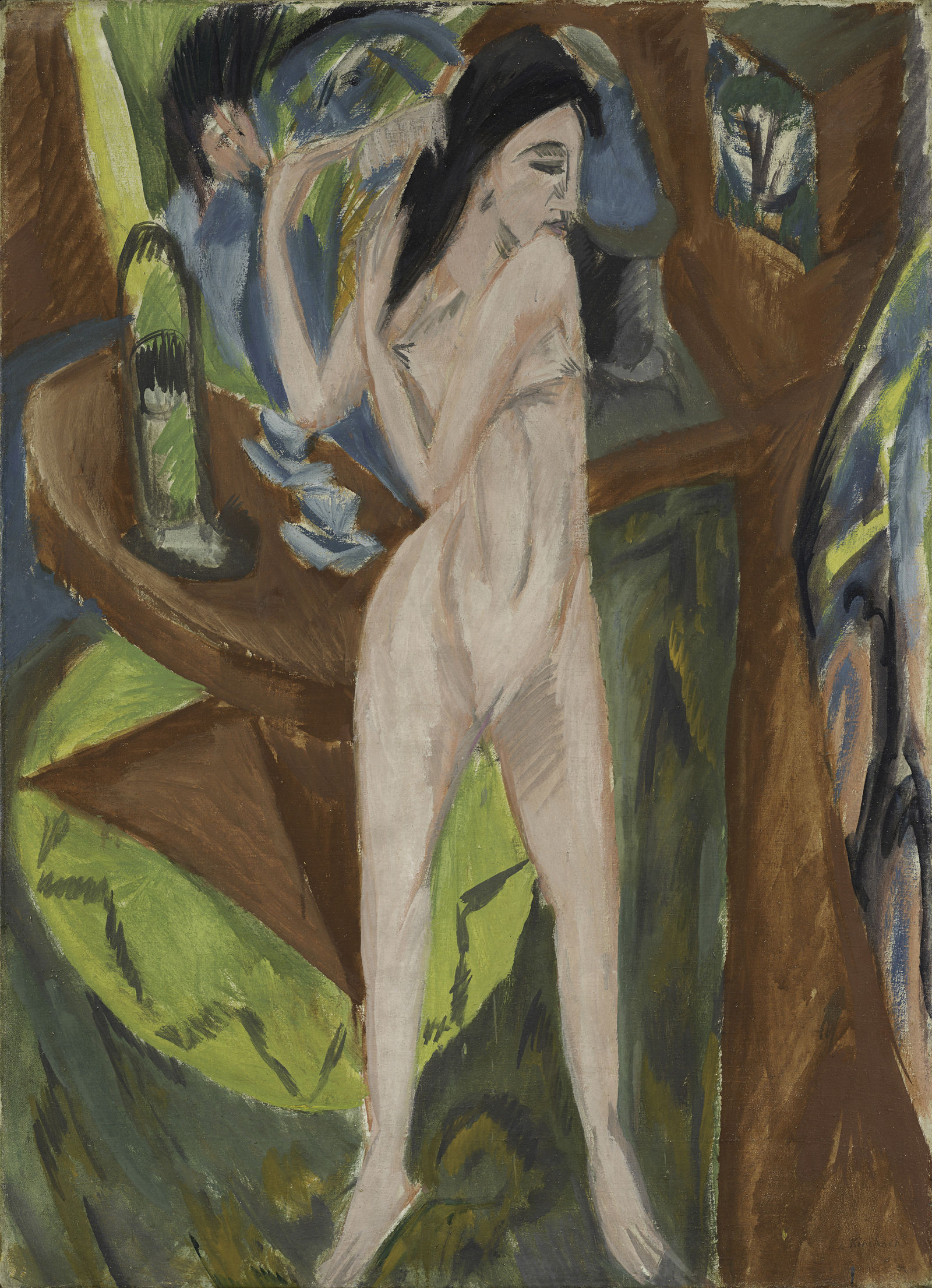

Given that questions concerning artistic value have always been a matter of dispute and are becoming ever more contested – especially so since modernity’s devaluation of technical skill in determining the standards of “good painting” or “good narration” – the concept of the canon has given rise to the most vehement disagreements. Why are so few women represented? Why almost exclusively white people? And why is it predominately Western art that is accounted for? To put it somewhat reductively, is it really only the work of dead white men that is valuable?

This was one among many points of criticism mounted against a 1994 book by literary scholar Harold Bloom, in which he defended The Western Canon. By the time of its publication, the so-called “canon wars” were already raging across university campuses in the United States. Students of color in particular were no longer willing to accept the glaring omission of their own experiences and identities in the canonical materials of their coursework.

Today we can indeed speak of a plurality of canons, but the debates nevertheless persist. Even if the most diverse, historically and presently marginalised groups of society have succeeded in gaining recognition for their artistic perspectives, Western-patriarchal-colonial hegemony remains ever-present. Even as, for example, the number of so-called “women’s exhibitions” increases or artists from the Global South receive more exposure, the fact remains that textbooks and collections continue to rehash the traditional narrative of white-male predominance.

A definitive conclusion on the question of what constitutes “good” work will, however, never be reached. Value judgments in art are always also tied to judgements of taste and market considerations. They are conditioned by the history, character and position of the person making the judgment. At least, though, there will always remain the opportunity to collectively interrogate, reflect on, reconsider, and renegotiate our perspectives time and again. Ideally, this will happen together, in its most polyphonous form.

Sonja Eismann is the co-editor of Missy Magazine and researches and writes about feminism and (pop) culture