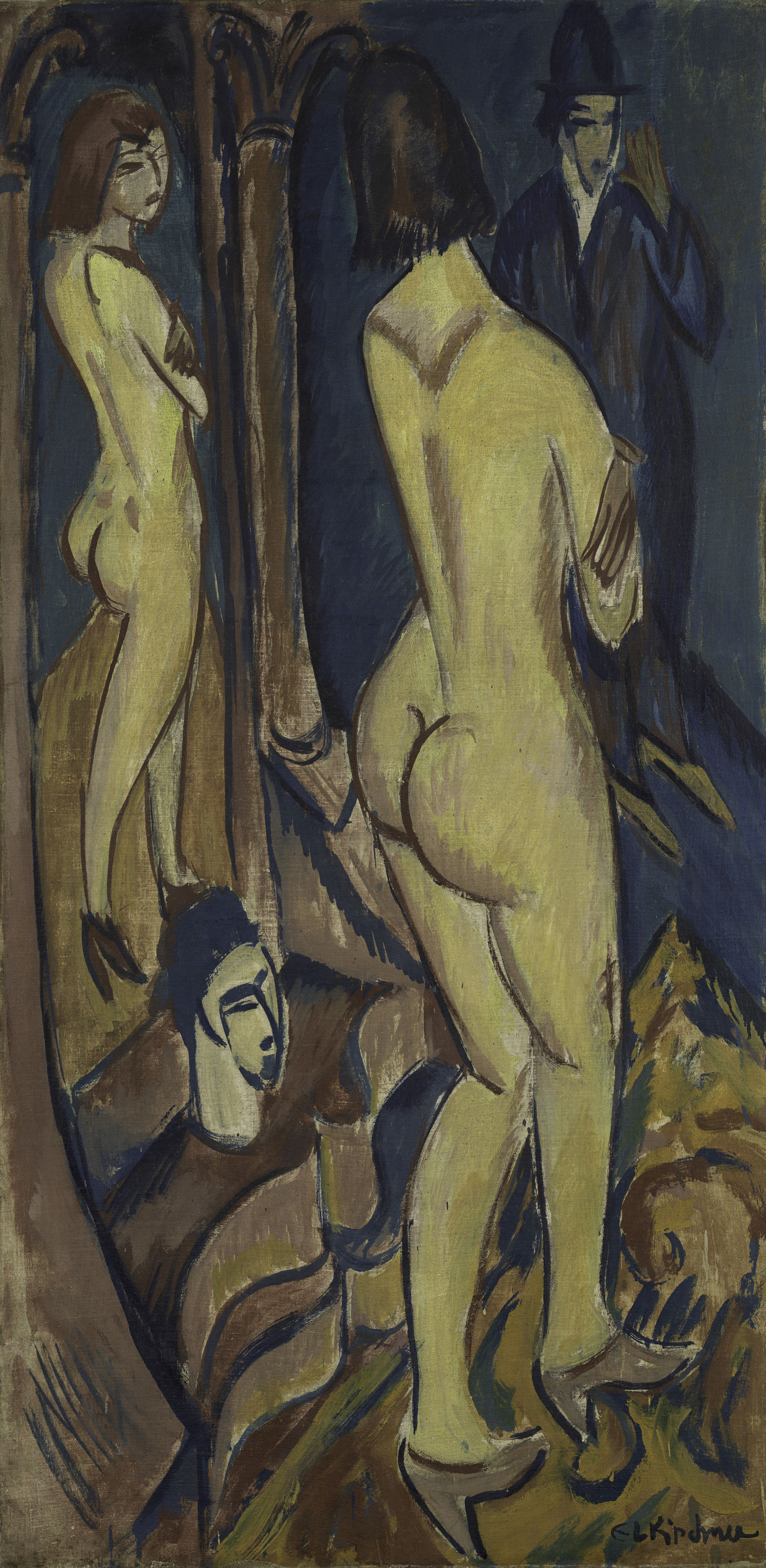

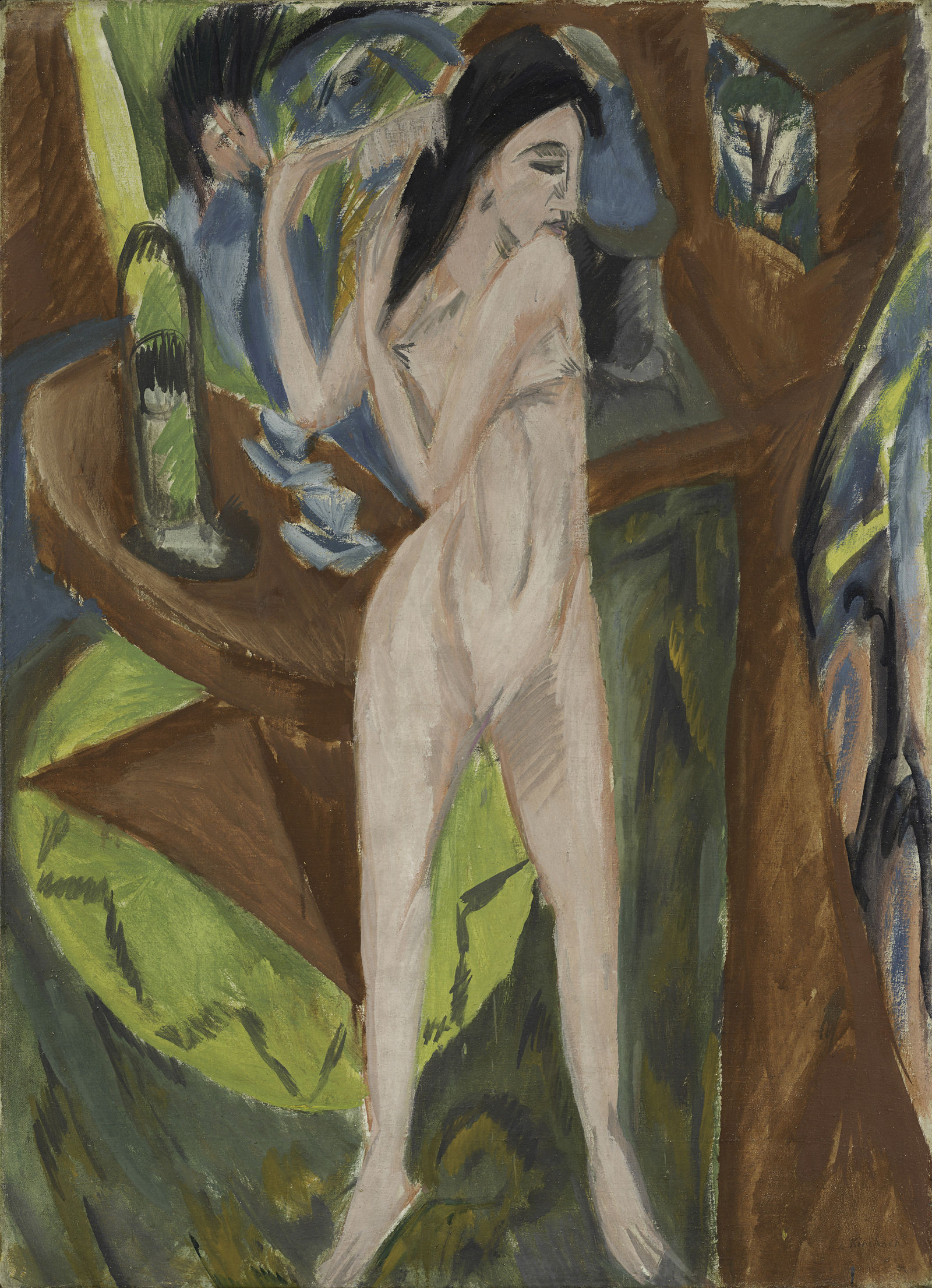

Check yourself out, make sure your look’s on point, pose. Striking a pose generally has negative connotations. But why, really? Is posing actually as narcissistic as society – the patriarchy – would have us believe?

Love songs, films and books always tell us how a woman is supposed to act under patriarchy: modest. Two of the most popular lines men in the media tell women are: “The most beautiful thing about you is that you don’t know that you’re beautiful” and “You don’t know how beautiful you are, but let me show you.” These sayings refer to a woman’s outer appearance, because this is considered to be her most important asset under patriarchy. But only insofar as men retain the agency to decide on it. What is read as a female body is viewed with pleasure so long as it remains marketable, conforms to sexist ideals and can be converted into capital.

Already in the 1970s and 1980s, the notion of self-confident posing was being shaped by the ballroom culture that emerged in different queer scenes throughout the US. It was specifically queer Black people and People of Colour who dominated the balls. Since they had been excluded from the queer white scene, they went on to make their own. The balls were above all venues for the practice of voguing, a style of dance extrapolated from the glamorous poses of famous models in fashion magazines. Queer Black people and People of Colour did not find themselves represented in fashion magazines like Vogue. In the ballroom scene they transformed conventional model poses into extravagant performances. They created spaces where they could celebrate their identities and bodies. Every so often, voguing culture became a trend in mainstream culture as was the case, for instance, in the 1980s with Madonna’s hit Vogue, which appropriated elements of ballroom culture. Just a few years ago FX and Netflix released the series Pose, which renewed the hype around voguing. For the majority of society, though, this only led to minimal change. It was, for instance, years before any of the Black trans actors received an Emmy nomination for their successes, whereas the only cis-gendered man in the series was repeatedly nominated. Far away from Hollywood, queer Black people – and especially Black trans women – are still subject to entirely other, incomparably extreme forms of discrimination. But their groundbreaking achievements as the pioneers of almost all movements are too seldom recognised, appreciated or remunerated.

The concept of posing is familiar to most people today primarily within the context of social media. Certain beauty standards are reinforced here as well. There are, for instance, a multitude of apps offering retouching tools to modify your appearance. What’s more, video and photo content is posted daily, detailing how to best orchestrate the supposedly correct and flattering picture pose. But apart from the continued reproduction of problematic ideals, the rising tide of self-representation on the internet has also had positive effects: the learned modesty of those who are not white cis-men keeps fading further and further into the background. Putting yourself on display is no longer viewed as purely negative. On the contrary, it is about self-empowerment and owning one’s rights to self and self-presentation. Women and queer people have been given the opposite messaging until now. As a result, many still constantly question themselves and frequently see themselves as inadequate.

This can be counteracted by self-curated representation in the digital realm, where individual bodies present their best looks via posing. Of course one must keep in mind that these channels do not exist outside of capitalism, the white system of domination and patriarchy. They are also subject to the norms and routines of a capitalist market and are filtered, included or excluded accordingly. Which people do persistent norms, discriminating filters and algorithms continue to oppress online? These algorithms and artificial intelligence filters are programmed by humans. Exclusionary practices exist here like they do in the rest of society. Studies from an intersectional feminist perspective have shown that forms of discrimination like sexism and racism are even amplified in artificial intelligence systems. Decisions are by no means more objective or just as the result of technological algorithms.

Heteronormative, white, patriarchal hegemony in society suggests to every person who is not a cis man that they are not valuable enough to take up space. Those marginalised people who oppose this and project a self-affirming public image are often denigrated as excessive, conceited, arrogant and attention-seeking. As a marginalised person, creating and claiming space for oneself and others in opposition to this violence is not only anti-patriarchal, but also political.

Neoliberal society requires that we pose every day anyway. White people must also package themselves in interviews, at dinner parties and events. Black people in particular sense this pressure to perform everywhere. Even in something as simple as a subway ride, they are exposed to demeaning looks, comments and racial profiling everyday. As a result, they are constantly made aware of how they seem to others. Many see themselves as if through an omnipresent mirror. Code-switching is a part of their everyday experience. Code-switching describes the change of habitus or language according to the person one is speaking with. It can thus refer to the language of a subculture, a dialect, slang or academic jargon. Code-switching is often used by marginalised groups to assimilate, protect themselves and ensure socioeconomic security. Especially in professional contexts, Black people are repeatedly confronted with racist stereotypes. They are often accused of being ill tempered, impolite and aggressive. Deliberately learning a public-facing personality that will not be seen as loud, challenging, brash or too quiet, uncertain, and not smart enough is a kind of performance that the word “work” cannot even begin to describe. It means giving up a part of yourself in public to avoid the threat of further violence.

Just existing within this system as a marginalised person makes posing and performing a necessary tool of survival.

In conclusion, the self-presentation of marginalised people is never reducible to something purely superficial or coquettish. Creating spaces to celebrate an otherwise oppressed self is important and in line with feminist practice. To assume that such a space simply exists for everyone within this social system is still an illusion.

Josephine Papke (sie/ihr/they/them, no pronouns) studied theatre and film studies and works in the cultural sector in a variety of ways, with an emphasis on negotiating the intersections of queerness, BIPOC identities and pop culture