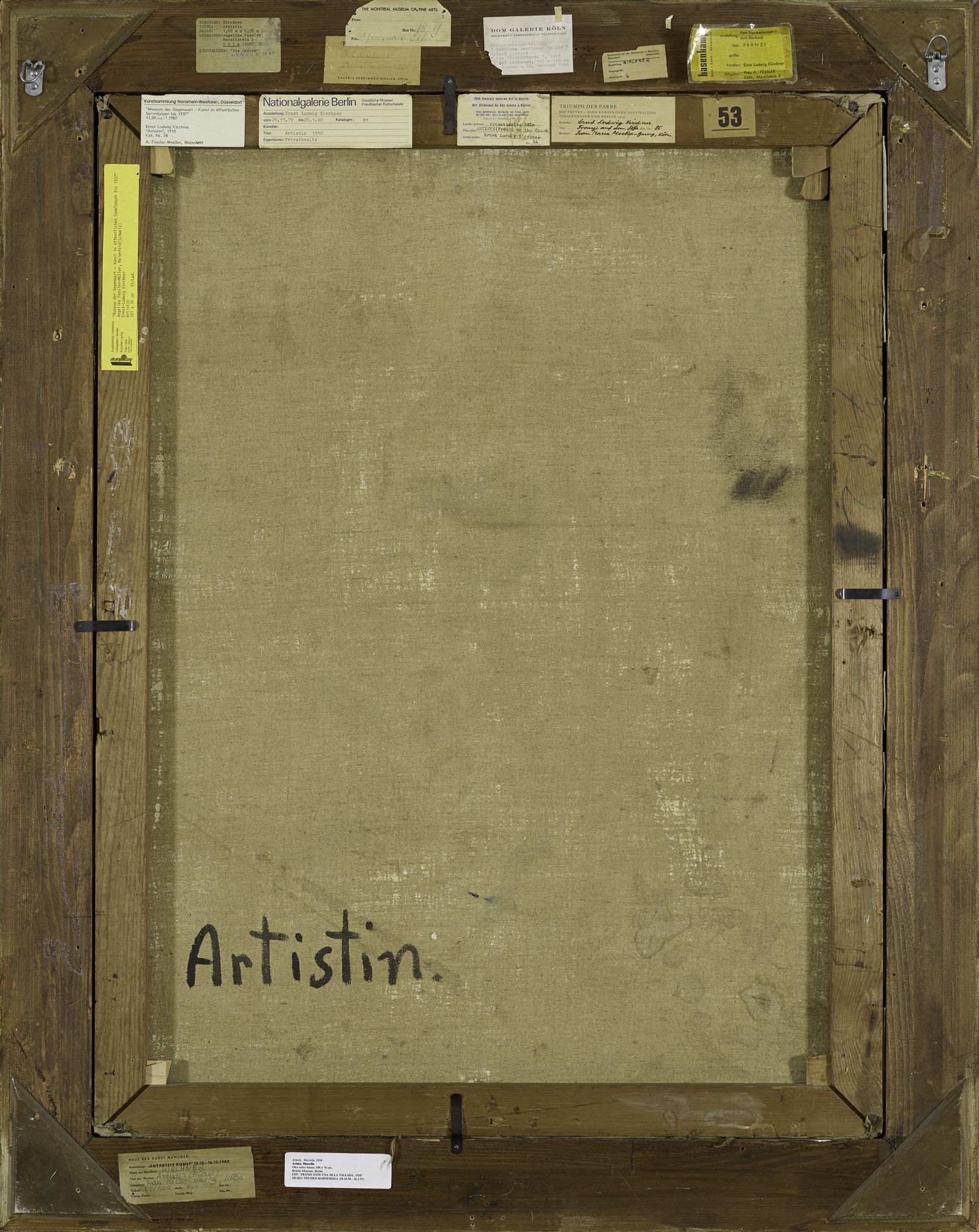

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Artistin

Rahmenmaß 120 × 95 × 5 cm

Provenienz

Der Kunstverein Jena erhielt das Gemälde 1917 als Vermächtnis seines Gründers Botho Graef (1857–1917). 1937 wurde es hier im Rahmen der nationalsozialistischen Aktion Entartete Kunst beschlagnahmt. Der Galerist Ferdinand Möller (1882–1956) übernahm das Werk im März 1940, um es im Auftrag des Deutschen Reichs ins Ausland zu veräußern. Stattdessen verblieb es in seinem Besitz. In das Brücke-Museum gelangte die Artistin 1997 durch einen Ankauf aus der Sammlung von Angelika Fessler-Möller (1919–2002), der Tochter des Kunsthändlers.

Exhibitions (selection)

- Der Angriff der Gegenwart auf die übrige Zeit. Künstlerische Zeugnisse von Krieg und Repression, 2023/24, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

Malgorzata Mirga-Tas. Sivdem Amenge. Ich nähte für uns. I sewed for us, 2023, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

How to Brücke-Museum: Ein Blick hinter die Kulissen , 2022/2023, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

1910: Brücke. Kunst und Leben, 2022, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

Flucht in die Bilder? Die Künstler der Brücke im Nationalsozialismus, 2019, Brücke-Museum, Berlin

Die Brücke 1905–1914, 2018/19, Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden

Großstadtrausch – Naturidyll. Kirchner – Die Berliner Jahre, 2017, Kunsthaus Zürich

... die Welt in diesen rauschenden Farben. Meisterwerke aus dem Brücke-Museum Berlin, 2016/17, Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte Oldenburg

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Retrospektive, 2010, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Literature (selection)

- Magdalena M. Moeller, Das Brücke-Museum Berlin, Prestel, München 1996.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke. La nascita dell´espressionismo, Ausst.-Kat. Fondazione Antonio Mazzotta Milan, Mazzotta, Milano 1999.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Die Brücke. Meisterwerke aus dem Brücke-Museum Berlin, Ausst.-Kat. Brücke-Museum Berlin, Hirmer Verlag, München 2000.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Neuerwerbungen seit 1988, Hirmer Verlag, München 2001.

Javier Arnaldo, Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke. Die Geburt des deutschen Expressionismus, Ausst.-Kat. Berlinische Galerie, Hirmer Verlag, München 2005.

Javier Arnaldo, Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke. El nacimiento del expresionismo alemán, Ausst.-Kat. Museo Thyssen-Bornesza Madrid/Fundación Caja Madrid, Madrid 2005.

Brücke und Berlin. 100 Jahre Expressionismus, Ausst.-Kat. Neue Nationalgalerie, Kulturforum Potsdamer Platz, Nicolai, Berlin 2005.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke-Museum Berlin, Malerei und Plastik. Kommentiertes Verzeichnis der Bestände, Hirmer Verlag, München 2006.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke Highlights, Hirmer Verlag, München 2007.

Staatssekretär für kulturelle Angelegenheiten des Landes Berlin, André Schmitz (Hg.), Im Zentrum des Expressionismus. Erwerbungen und Ausstellungen des Brücke-Museums Berlin 1988 - 2013. Ein Jubiläumsband für Magdalena M. Moeller, Hirmer Verlag, München 2013.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Meisterstücke. Die schönsten Neuerwerbungen des Brücke-Museums, Ausst.-Kat. Brücke-Museum, Hirmer Verlag, München 2013.

Magdalena M. Moeller und Rainer Stamm (Hg.), ... die Welt in diesen rauschenden Farben. Meisterwerke aus dem Brücke-Museum Berlin, Ausst.-Kat. Landesmuseum Oldenburg, Hirmer Verlag, München 2016.

Magdalena M. Moeller (Hg.), Brücke Museum Highlights, Hirmer Verlag, München 2017.

Meike Hoffmann, Lisa Marei Schmidt, Aya Soika für das Brücke-Museum (Hg.), Flucht in die Bilder? Die Künstler der Brücke im Nationalsozialismus, Ausst.-Kat. Brücke-Museum , Hirmer Verlag, München 2019.

Brücke-Museum, Lisa Marei Schmidt, Isabel Fischer (Hg.), 1910. Brücke. Kunst und Leben, ausstellungsbegleitende Zeitung, Brücke-Museum, Berlin 2022.

Details

Tags

Bildgattung: Figurenbild, Bildnis

Schlagwort: Melancholie, Interieur

Album: Tiere

Iconclass

Mädchen, junge Frau

Katze

Behälter aus Glas: Flasche, Gefäß, Vase

den Kopf in einer Hand halten; dabei den Ellenbogen auf eine Erhebung oder auf ein Knie stützen

Schuhe, Sandalen

Couch, Sofa, Polsterbank

Hausinneres

Mensch und Tier

Inscription/Signature

Signiert oben rechts:

EL Kirchner (Signatur)

Rückseitig auf dem Bildträger:

Artistin (Bezeichnung)

Rückseitig auf dem Bildträger:

Artistin (Beschriftung)

Inventory Number

1/97

Catalog Number

Gordon 125