The Brücke Artists and the National Socialist Action “Degenerate Art”

Meike Hoffmann

Research Assistant / Freie Universität Berlin

The Nazis’ “Degenerate Art” campaign began at the end of June 1937 and lasted officially until the end of June 1941. It involved the systematic confiscation and removal (seizure) of all Modernist artworks from public institutions in Germany, as well as their condemnation in exhibitions, at public events, and in films and publications. The term “degenerate”, which originally comes from evolutionary biology, found its way into art and cultural theory via the pessimistic world view that arose in the late 19th century. During the 1920s, the defamation of Modernist art by reactionary circles increased just as the avantgarde art scene was flourishing. Under the Nazis, “degenerate” became a fixed term in the vocabulary of their propaganda, and with their “Degenerate Art” campaign it gained considerable force in the condemnation of art that had become unwelcome. By reducing the criticism down to the word “degenerate”, the Nazis eliminated the technical language of art history as evaluative criteria and linked art judgements to the category of racial ideology. Hence, any art trend that went beyond the academic-idealistic norm could be subsumed under it.

The Brücke artists were particularly hard hit by the campaign. Although, even after 1933, they could still harbour hopes that supporters and patrons from Nazi circles would present them to the regime as being paragons of an art that championed the German nation, their works were those most frequently labelled “degenerate” and therefore removed from museums and exhibition halls after 1937. Hence, according to the latest status of research, of the more than 21,000 works confiscated across the Reich, 1,082 were by Emil Nolde, 762 by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, 760 by Erich Heckel, 706 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 509 by Max Pechstein, and 404 by Otto Mueller. The domination of Expressionist works in general and those of the Brücke artists in particular itself reflected museums’ acquisition policies during the interwar years. During that period, it had become possible to integrate works by living artists into state collections for the first time. With the opening of the Crown Prince’s Palace, as far back as 1919 Ludwig Justi as Director of the Nationalgalerie had sounded the clarion call for museum reform, which duly followed in subsequent years, and indeed reached even the most distant provinces. In the Palace’s Neue Abteilung (Department for the New), Expressionism was considered the German contribution to international Modernism and was therefore judged to help get the country back on its feet as a cultural nation after its defeat in the First World War.

The central role assigned to the Brücke artists as founders of Expressionism in this quest to establish a new German identity initially saved them even after the Nazis came to power in 1933, but over time this was gradually reversed. From 1937 onwards, after the compulsory alignment of all areas of public life to Nazi ideology, their works were placed firmly in the spotlight in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich. From July 19 to the end of November 1937, several hundred of the seized works were exhibited – with a great deal of effort having gone into their presentation – specifically in order to expose them to the visitors’ scorn. Joseph Goebbels developed the idea by way of contrast with the first “Great German Art Exhibition” in the newly built “Haus der Deutschen Kunst”, which opened one day earlier. After debuting in Munich, the “Degenerate Art” exhibition toured numerous locations in Germany and Austria. Even before that, there had been defamatory exhibitions on a regional level, but now they were supported by the Nazi regime’s government. The latter used the campaign against Modernism, which was accompanied everywhere by detailed reporting and was even implemented by way of entertainment films, quite deliberately to stir up feeling against the parliamentary democracy of the interwar years, which had supposedly opened the door to the “Jewish-Bolshevik global conspiracy” that was ostensibly causing the destruction of German culture.

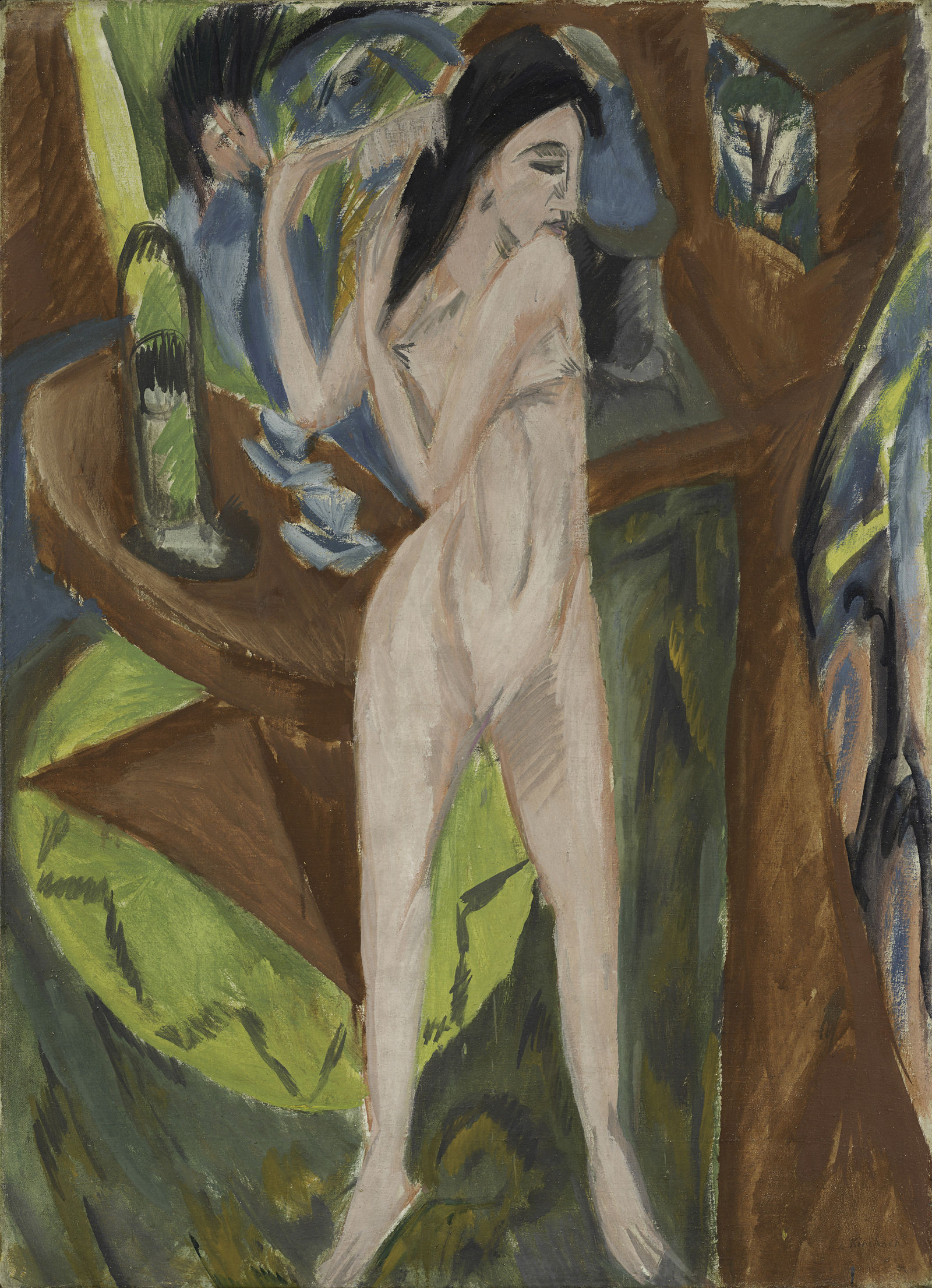

Brücke-Museum owns an entire series of masterpieces that were seized from other museums in 1937 as part of the “Degenerate Art” campaign: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Marzella, 1910 (formerly Jenaer Kunstverein), Nude Woman Combing her Hair, 1913, and The Garden Café, 1914 (both formerly Städtisches Museum für Kunst and Kunstgewerbe Halle a.d. Saale) and Self-Portrait, 1914 (formerly Hamburger Kunsthalle); Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s Roman Still Life, 1930 (formerly Nationalgalerie Berlin); Erich Heckel’s Three Women Against a Red Cliff, 1921 (formerly Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim); and Otto Mueller’s Three Nudes in the Landscape, 1922 (formerly Kaiser Wilhelm Museum Krefeld). What fate awaited the works of art after they had been seized by the Nazis? How did they end up in Brücke Museum and what is their legal status today?

In early 1938, Herman Göring (at that time Head of the Luftwaffe and Nazi Economics Minister) succeeded in selling some of the works abroad in exchange for foreign currency. Subsequently, on May 31, 1938, the “Law for the Withdrawal of Degenerate Art” (RGBl I, p. 612) was passed, whereby the Reich finally gained the power to dispose of the seized artworks. An auction of 125 masterpieces held in the neutral nation of Switzerland on June 30, 1939, kicked off the process, and this was followed by private sales of the extensive remaining stocks via selected art dealers. After the end of the Second World War, the law was not revoked by the Allied Control Council and in September 1948 the Museum Council of Northwest Germany confirmed the resolution that the works had not been seized from private individuals as part of Nazi persecution, but rather removed from public collections based on aesthetic principles. There was to be no reverse transaction that would represent a new injustice to the people who had worked to preserve the works, it resolved. Hence, the change of ownership following the seizure is still legally recognized to this day.

Meike Hoffmann is a lecturer in provenance research and Nazi art policy at the Freie Universität Berlin. There, she is Director of the “Degenerate Art” Research Unit as well as the Mosse Art Research Initiative (MARI). She most recently co-curated the exhibition Escape into Art? The Brücke Painters in the Nazi Period (with Aya Soika and Lisa Marei Schmidt, Brücke Museum, Berlin and Kunsthaus Dahlem, 2019).

On this history and reconstruction of the “Degenerate Art” confiscation campaign, see the web portal of the “Degenerate Art” research unit at the Freie Universität Berlin, complete with database.